English version below

Gli agricoltori palestinesi iniziano il raccolto delle olive fra gli attacchi dei coloni

Le restrizioni dovute alla pandemia sono diventate un ulteriore strumento di vessazione per gli agricoltori palestinesi che devono lottare ancora di più per accedere alle proprie terre, mentre i coloni israeliani approfittano della situazione e saccheggiano i raccolti nell’Area C

testo e foto di archivio di Fareed Taamallah*

traduzione di Maria Elena Fantoni

«Non posso raggiungere la mia terra ed è un’ingiustizia. Di quale pace stanno parlando?! Pace significa poter riavere indietro la terra che mi hanno portato via» afferma Helweh Abu Ras guardando tristemente alle montagne di fronte a casa sua dov’è situato l’insediamento illegale di Eli, costruito sulla sua proprietà.

Helweh Abu Ras, agricoltrice palestinese di settantasette anni del villaggio di As-Sawiya, ha concesso un’intervista al Middle East Eye durante le preparazioni per il periodo del raccolto delle olive, che inizia questa settimana. Ciò nonostante, non è per niente sicura che potrà accedere alla sua terra per portare avanti il raccolto.

Il raccolto delle olive è considerato una delle fonti principali di sostentamento per migliaia di famiglie palestinesi che, tuttavia, incontrano molte difficoltà a causa degli attacchi dei coloni israeliani che prendono di mira questo settore vitale.

A partire dagli accordi di Oslo del 1993, la Cisgiordania è stata divisa in tre zone: A, B e C. L’area C, che rappresenta approssimativamente i due terzi della Cisgiordania occupata, è sotto pieno controllo militare israeliano. Contemporaneamente, sempre in Cisgiordania, si contano 200 insediamenti israeliani con più di 600.000 coloni che vivono contravvenendo alle leggi internazionali.

I palestinesi che vivono in queste aree si sono visti confiscare le proprie terre o averne limitato l’accesso, diventando allo stesso tempo vulnerabili agli attacchi violenti dei coloni.

Lo stabilimento di insediamenti nei territori palestinesi occupati è sempre stata una fonte primaria di vulnerabilità fra i palestinesi. Li ha deprivati della proprietà e di una delle risorse principali di sostentamento. Ha portato a restrizioni negli accessi e causato attacchi violenti sugli abitanti da parte dei coloni ebrei.

Il villaggio di As-Sawiya, a sud di Nablus, è circondato da due insediamenti ebraici: Eli a est e Rehelim a nord.

Nel 1984 le autorità a capo dell’occupazione israeliana confiscarono più di millecinquecento dunum (un dunum equivale approssimativamente a mille m2 n.d.t.) di terra appartenente agli abitanti di As-Sawiya, dieci dei quali appartenevano alla famiglia di Helweh. Da allora a tutti i proprietari, inclusa Helweh, è stato negato il diritto di coltivare le proprie terre, nelle quali sono state piantate, con le parole di Helweh, «le migliori qualità di olive, fichi e uva».

Nel 1991, le autorità israeliane confiscarono centinaia di dunum dal territorio di As-Sawiya al fine di costruire l’insediamento di Rehelim a nord del villaggio. Decine di proprietari terrieri palestinesi persero le loro terre e fu loro negata l’accessibilità alle piantagioni di loro proprietà vicino all’insediamento.

Helweh non poté più accedere ad altri undici dunum della sua proprietà proprio a causa della loro prossimità con l’insediamento. «Abbiamo presentato una denuncia all’ufficio di coordinamento e sottoposto documenti che provano la proprietà della terra al tribunale israeliano che di risposta ha stabilito che possiamo accedere ai terreni due giorni all’anno. Tuttavia, anche questa ingiusta decisione non è stata rispettata», afferma Helweh.

Per poter entrare nella sua terra, deve “coordinarsi” con l’esercito israeliano, processo solitamente lungo e spesso fallimentare.

Gli agricoltori palestinesi deprivati del loro raccolto

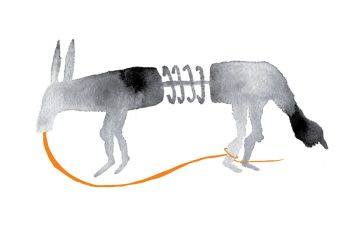

Se gli agricoltori provano a raggiungere la propria terra senza coordinarsi con l’esercito israeliano, si espongono a un grande pericolo. «Nel 2007 ho provato a entrare nei miei terreni situati vicino all’insediamento di Rehelim, ma i coloni sono arrivati e mi hanno picchiato, hanno preso il mio asino e i miei attrezzi e mi hanno cacciato dalla mia terra», racconta Helweh. Nonostante sia stata fatta denuncia all’amministrazione civile, gli assalitori non sono stati ritenuti colpevoli.

Dal 2006 Helweh non ha più raccolto un singolo frutto, gli alberi si sono seccati a causa delle poche cure e a causa della presenza delle acque reflue che dall’insediamento vengono deliberatamente scaricate fra i frutteti. «Prima che l’insediamento fosse costruito, raccoglievamo venticinque secchi di fichi al giorno da queste terre, ma ora il numero è zero», afferma Helweh.

In teoria, il “coordinamento” permette che i proprietari possano accedere alle proprie terre due volte all’anno, una in corrispondenza del periodo dell’aratura, l’altra in autunno per il raccolto delle olive.

«L’esercito isreaeliano ci consente di poter accedere alla nostra proprietà due volte all’anno, ma la terra ha bisogno di quattro o cinque giorni di lavoro. Di solito chiamiamo volontari palestinesi e internazionali ad aiutarci a raccogliere le olive, ma spesso una larga parte degli alberi rimane da fare, perché il tempo che ci è concesso è insufficiente», spiega al Middle East Eye Arafat Abu Ras, il figlio di Helweh.

A seguito dell’incuria, gli alberi si sono seccati e non producono più molte olive. «Prima del 2012, questo appezzamento di terra produceva trecento litri d’olio, ora ne produce più o meno cento», racconta Helweh.

I palestinesi che vivono nei territori della Cisgiordania occupati da Israele lamentano i frequenti attacchi dei coloni ebrei, che spesso compiono atti di violenza fisica, vandalismo e distruzione di terre agricole.

Molti coltivatori di As-Sawiya riportano di venir derubati del loro raccolto di olive ogni anno. Nell’ultima stagione, i coloni hanno saccheggiato i raccolti di tre coltivatori, i quali hanno sporto denuncia. Nessun colono è stato ritenuto colpevole e nessuno ha compensato gli agricoltori per la loro perdita.

Il villaggio di Burin

Doha Asous, cinquantanove anni, è un’agricoltrice del villaggio di Burin, a sud di Nablus. Attorno a Burin vi sono tre insediamenti: Yitzhar, costruito nel 1984 nella parte più meridionale di Burin, dove vivono i coloni più violenti; Har Brakha, costruito nello stesso anno nella parte settentrionale, e Givat Ronen, un avamposto più piccolo, stabilito negli anni novanta sulla montagna a nord di Burin.

Doha è proprietaria di undici dunum di terra con duecento ulivi, circondati dall’avamposto di Givat Ronen. Doha ha dichiarato a Middle East Eye che, mentre a lei non è permesso coltivare la propria terra, i coloni ogni anno rubano il suo raccolto e abbattono i suoi ulivi.

Nel 2015 i coloni hanno dato fuoco agli uliveti di Doha, dopo aver depredato il raccolto. Per l’ennesima volta, è stata fatta una denuncia, ma senza risultato.

“L’anno scorso l’esercito israeliano ci ha dato il permesso di accedere alle terre per un giorno durante il raccolto. Abbiamo visto che i coloni avevano già sottratto il raccolto e che avevano abbattuto gli alberi. Abbiamo riportato il fatto alla polizia e ai gruppi per i diritti umani, ma non ci è giunta notizia di nessun colono che sia stato arrestato», ha dichiarato Doha.

Gli abitanti di Burin hanno riportato che, nel solo 2020, cinquemila alberi sono stati dati alle fiamme dai coloni, senza che un singolo colone sia stato mai ritenuto colpevole.

L’impunità dei coloni

La violenza dei coloni è cosa consueta nella Cisgiordania occupata. Aumenta principalmente durante il periodo del raccolto, ma è raramente perseguita dalle autorità israeliane, mentre le autorità palestinesi non hanno giurisdizione sui coloni israeliani. Dopo ripetuti attacchi agli agricoltori palestinesi l’esercito israeliano ha proibito ai proprietari di accedere alle proprie terre, se vicine a un insediamento. Invece di proteggere i coltivatori rinforzando le leggi sui coloni. In questo modo, hanno creato il concetto di “impunità” dei coloni. «Riteniamo che l’esercito israeliano cospiri con i coloni la distruzione dei nostri alberi e le razzie dei nostri raccolti. Ogni anno l’esercito ritarda la concessione dei permessi, permettendo ai coloni di approfittare dei rallentamenti per impadronirsi del nostro raccolto e per poi vandalizzare gli alberi», dichiara Helweh al Middle East Eye.

Come riportato da Yesh Din, organizzazione israeliana per i diritti umani, delle 263 indagini portate avanti dalla polizia e monitorate dall’organizzazione stessa fra il 2014 e il 2019, soltanto il 9% ha portato ad azioni penali contro i responsabili, mentre le restanti indagini si sono chiuse senza incriminazioni.

Nel 2017 Helweh è stata investita da una jeep militare sulla strada principale mentre si recava ai suoi terreni, episodio che le ha causato lesioni molto gravi. Rimasta in coma in terapia intensiva per dieci giorni, dopo che i medici le hanno dovuto asportare la milza, Helweh ha scampato miracolosamente la morte. «Ci siamo recati al tribunale israeliano per ottenere un risarcimento e affinché il colpevole fosse punito ma, a distanza di tre anni dall’incidente, non abbiamo ancora ottenuto nessun risultato».

Approfittando della pandemia

Nei primi cinque mesi del 2020 l’Ufficio per le Nazioni Unite degli affari umanitari ha documentato 143 attacchi da parte di coloni israeliani, di cui circa il 55% fra marzo e aprile, a coincidere con lo scoppio dell’emergenza COVID-19.

L’esercito israeliano e i coloni ebrei hanno approfittato delle restrizioni nei movimenti e delle misure di distanziamento fisico imposte dalle autorità palestinesi alle loro comunità per contenere la pandemia. Ad As-Sawiya, mentre i palestinesi erano in lockdown, i coloni di Rehelim hanno provato a espandersi appropriandosi di altre terre fra quelle situate subito sotto l’insediamento. Hanno piantato una tenda, sradicato alberi e installato filo spinato, cosa che ha costretto gli abitanti del villaggio a infrangere il lockdown per protestare. Gli abitanti sono temporaneamente riusciti a rimuovere la tenda e il filo spinato; nonostante questo, ogni giorno, i coloni, protetti dall’esercito, ritornavano per cercare di impossessarsi dei terreni.

Il mese scorso i coloni dell’insediamento illegale di Rehelim hanno fatto irruzione in alcuni uliveti del villaggio e abbattuto circa sessanta alberi di proprietà di tre palestinesi abitanti di As-Sawiya.

Helweh e Doha hanno dichiarato al Middle East Eye che sia ad As-Sawiya che a Burin l’esercito non ha loro permesso di arare le terre vicine agli insediamenti. Non sanno se le forze armate permetteranno loro di raccogliere le olive, in modo particolare ora, alla luce della sospensione del coordinamento di sicurezza.

Helweh rimpiange la sua terra e i suoi alberi: “Sono addolorata per la perdita dei miei terreni, dove coltivavo orzo, sesamo, grano e i fichi della miglior qualità. Ho settantasette anni e non sono sicura che vivrò abbastanza per vedere la mia terra rinascere”. Spera che Dio le renderà giustizia, perché l’occupazione e il suo sistema legale non lo faranno.

Questo articolo è stato pubblicato su Middle East Eye il 6 ottobre 2020

*Fareed Taamallah è un giornalista, attivista per la pace e agricoltore palestinese, vive nella città di Ramallah, in Cisgiordania.

da L’Almanacco de La Terra Trema. Vini, cibi, cultura materiale n. 19

16 pagine | 24x34cm | Carta cyclus offset riciclata gr 100 | 2 colori

Palestinian Farmers starting olive harvest amid settlers’ attacks*

By: Fareed Taamallah

“I can’t reach my land and this is an injustice. What kind of peace are they talking about?! Peace means that I can regain my stolen land” says Helweh Abu Ras whilelooking sadly at the mountain across from her house where the illegal settlementof Eli is situated,built on her property.

Helweh Abu Ras, 77 years old, a Palestinian farmer woman from the village of As-Sawiya, spoke to MEE while preparing for the olive harvest season which starts this week. However, she is not sure if she will be allowed to access her land to harvest.

The olive harvest is considered a main source of livelihood for thousands of Palestinian families, but they face many obstacles due to the Israeli settlers’ attacks targeting this vital sector.

Since the 1993 Oslo Accords, the West Bank has been divided into three zones, known as Area A, B and C. Area C, representing roughly two-thirds of the occupied West Bank, is under full Israeli military control. Meanwhile, Israeli settlements number around 200 in the West Bank, with more than 600,000 settlers living in contravention of international law.

Palestinians living in these areas have seen lands confiscated or their access restricted, while becoming vulnerable to violent attacks by settlers.

The establishment of settlements in the Occupied Palestinian Territories has been a key source of vulnerability for Palestinians. It has deprived them of their property and of one of the main sources of livelihood. It has also led to access restrictions and generated violent attacks on villagers by Jewish settlers.

The West Bank village of As-Sawiya -south of Nablus- is surrounded by two Jewish settlements: Eli from the east and Rehelim from the north.

In 1984 the Israeli occupation authorities confiscated more than 1500 dunums belonging to the villagers of As-Sawiya, 10 dunums of which belong to Helweh’s family. Since then, owners of the land, including Helweh, have been denied the right to cultivate their property planted with “the best types of olives, figs and grapes” as she says.

In 1991, the Israeli authorities confiscated hundreds of dunums of As-Sawiya land in order to build the settlement of Rehelim to the north of the village. Dozens of Palestinian property owners lost their land and were denied entry to their groves located near the settlement.

Helweh wasdenied access to another 11-dunums of her propertydue to its “proximity” to the settlement. “We filed a complaint to the coordination office, and we submitted documents to prove our land ownership to the Israeli court which ruled that we can access our land two days a year only, but even this unjust decision was not carried out,” says Helweh.

In order to access her land, she needs to “coordinate” with the Israeli army which is usually a long and often unsuccessful process.

Palestinian farmers’ deprivationof their harvest:

If the farmers try to reach the land without coordination with the Israeli army, they expose themselves to severe danger. “In 2007 I tried to enter my land near the settlement of Rehelim, but the settlers came and beat me up, stole my farm equipment and my donkey and expelled me from my land.” Helweh says. A complaint was submitted to the Civil Administration, but the assailants have not been held accountable.

Since 2006, Helweh has not picked a single fruit from her farm, the trees have dried up because of neglect, and because of the sewage water which is deliberately released from the settlement onto the groves. “Before the settlement was built, we used to harvest 25 full buckets of figs daily from this farm, but now the number is zero” Helweh says.

In theory, landowners are allowed access to their property by means of the “coordination” process twice a year, namely in spring during the plowing season, and in autumn during the olive harvest.

“The Israeli army allows us to enter our property twice a year but the land needs 4-5 days of work. Usually, we call Palestinian and international volunteers to help with olive picking, but often a large number of olive trees remain un-harvested, because the time allowed to us is insufficient to harvest all the trees”. Arafat Abu Ras, the son of Helweh, tells MEE.

Due to the poor reclaim and care for the land, the trees have dried up and no longer bear many olives. “Before 2012, this plot of land used to produce 300 litres of oil, while now it only produces about 100 litres,” says Helweh.

Palestinians living in the Israeli-occupied West Bank complain of frequent attacks by Jewish settlers, which often include acts of physical violence, vandalism and the destruction of Palestinian farmlands.

Many farmers from As-Sawiya complain that their olive harvest is stolen every year by settlers. Last season, the settlers looted the harvest of three farmers, who filed a complaint. No settler has been held accountable and no one compensated the farmers for their loss.

Burin Village:

Doha Asous, 59 years old, is a woman farmer from the village of Burin, south of Nablus. Three settlements surround Burin: Yitzhar, built in 1984 on the southern part of Burin where the most violent settlers live; Har Brakha, built in the same year on the northern part, and a smaller outpost called Givat Ronen, established during the 90s above the northern mountain of Burin.

Doha owns 11 dunums of land planted with 200 olive trees and surrounded by the Givat Ronen outpost. Doha tells MEE that while she is not allowed to cultivate her land, the settlers instead steal her olive harvest and chop her olive trees every year.

In 2015 the settlers set fire to Doha’s olive groves, after stealing the harvest. Again, they filed a complaint but with no result.

“Last year the Israeli army gave us a one-day permission to get to our land during the olive harvest. We found the settlers had already stolen the harvest and chopped the trees. We complained to the police and the human right groups, but we were never informed about any of the settlers being arrested”. Doha says.

The villagers of Burin reported that 5000 trees have been torched by the settlers in 2020 alone, without one single settler assailant being held accountable.

Settler’s impunity

Settler violence is commonplace across the occupied West Bank. It mainly increases during the olive harvest season, but is rarely prosecuted by the Israeli authorities, as the Palestinian Authority has no jurisdiction over Israeli settlers.

After repeated settler attacks on Palestinian farmers, the Israeli military forbade Palestinian farmers from entering their own land if it lies near a settlement. Instead of protecting the farmers by enforcing the law on the settlers. They have in this way generated the concept of settler “impunity”.

“We believe that the Israeli army is conspiring with the settlers to destroy our trees and steal our harvest. Every year, the army delays the issuing of the permits, allowing the settlers to take advantage of this delay to steal our olive harvest, and then vandalize the trees” Helweh tells MEE.

As reported by the Israeli human rights organization Yesh Din, of the 273 Police investigations tracked by the organization between 2014 and 2019, only 9% led to the prosecution of offenders while the other investigations were closed without indictment.

In 2017, Hilweh wasran overby a military jeep on the main street while she was heading to her land causing her a severe injury. She remained in a coma at the intensive care unit for 10 days, then the doctors removed her spleen, however she miraculously escaped death. “We went to the Israeli courts to obtain compensation and to punish the perpetrator, but 3 years after the incident we still have not obtained any success”.

Taking advantage of the pandemic:

In the first five months of 2020, OCHA documented 143 attacks attributed to Israeli settlers, around 55 per cent of which were recorded during March and April, coinciding with the outbreak of COVID-19. The Israeli army and the Jewish settlers took advantage of the access restrictions for the Palestinian communities, and of the physical distancing measures, imposed by the Palestinian Authority to contain the pandemic.

In As-Sawiya,while Palestinians were in lockdown, the settlers of Rehelim attempt grabbing more of the village land situated below the settlement. They put up a tent, uprooted trees and installed barbed wire, which forced the villagers to break the lockdown to protest. They succeeded in removing the tent and the wires temporarily, but every day the settlers, protected by the army, try to come back to seize the land.

Last month, the settlers from the illegal settlement of Rehelim broke into Palestinian-owned groves of the village, before proceeding to chop off about 60 trees, which belonged to three Palestinian villagers from As-Sawiya.

Helweh and Doha told MEE that both in As-Sawiya and in Burin, the army did not allow them to plow the land next to the settlements. They do not know whether the army will allow them to harvest their olives, especially in light of the suspension of the security coordination.

Hilweh bemoans her land and trees. “I feel sorry for the loss of my land where I used to grow barley, sesame, wheat, and the best kind of figs. I am 77 years old now and I am not sure I will live long enough to witness the restoration of my land.” She hopes that God will grant her justice, because the occupation and its legal system will not.

*This story was published on Middle East Eye on October 6th,2020

Last modified: 29 Gen 2021